British Journal of Urology, Volume 52, Pages 147-150. April 1980.

Paediatric Surgical Unit, The Children's Hospital, Sheffield

British Journal of Urology, Volume 52, Pages 147-150. April 1980.

Paediatric Surgical Unit, The Children's Hospital, Sheffield

Summary--Phimosis, defined as scarring of the tip of the prepuce, was studied prospectively in a series of 23 boys aged 4 to 11 years. There was little to support the contention that the condition is caused by trauma, or by ammoniacal or bacterial inflammation of the prepuce, could any other aetiological factor be identified. Histological examination of the foreskin showed the appearances of Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans in 20 of the 21 specimens submitted for study.

The usual reason for referral, and the commonest indication for circumcision, is phimosis

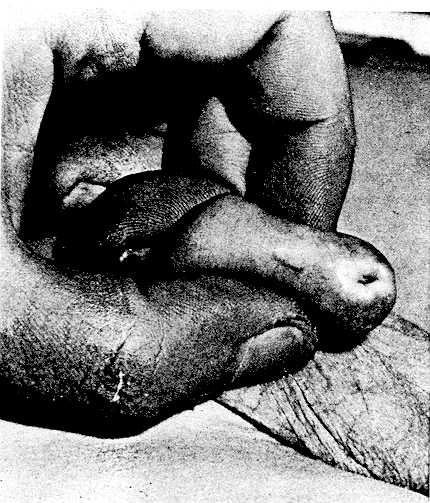

, but experience suggests that this condition is over-diagnosed and many unnecessary circumcisions performed in consequence. True, from its Greek derivation (φ ιμωσ ις, muzzling), the term might be applied whenever the foreskin cannot be retracted to reveal the glans penis, but Gairdner (1949) demonstrated that in young boys non-retractability of the foreskin is a normal finding and is due to the persistence of developmental adhesions between glans and prepuce. These break down spontaneously with the passage of time and, without interference, full retractability of the foreskin can be expected in almost all boys by their early teens (Oster, 1968). Non-retractability of this type requires no treatment and the term phimosis is best avoided in this situation since it implies the existence of pathology when there is none. On the other hand, there are cases where the tip of the prepuce loses its normal suppleness and becomes scarred, resulting in secondary non-retractability. The appearances are unmistakable (Fig. 1) and clearly pathological; we confine the term phimosis

exclusively to cases of this type.

Little is known of this condition. Its aetiology has been variously described to the trauma of forcible retraction (Twistington Higgins et al., 1951), to ammonia dermatitis (Robarts, 1962) or to repeated episodes of bacterial balanoposthitis (Campbell, 1951). Its natural history is unknown and its histological features have not been adequately described. That circumcision is the only possible treatment has never been questioned. In view of this lack of knowledge we elected to study a series of cases in detail.

A prospective analysis was made of 23 consecutive new cases of phimosis seen in the first 9 months of 1978. At the initial out-patient attendance full details of the history and physical examinination was entered on a pro forma. All of the patients proceeded to circumcision, where the operative findings were noted, the urine and the bacterial flora of the prepuce cultured, and the operative specimen submitted for histological examination.

scarringof the tip of the prepuce is plainly seen.

Clinical Findings

The Age distribution of the patients is shown in Figure 2. The mean duration of symptoms was 3.1 months (range 2 days to 14 months. Seven patients complained of poor urinary stream, 6 of dysuria, 4 of irritation or soreness of the prepuce, 2 of non-retractability of the foreskin and one of haematuria, whilst 3 boys admitted to no symptoms. One boy described a vesicular eruption on his prepuce at the onset of the disease, but in the remainder the process began insidiously. There were no apparent precipitating factors, nor any history of a change of clothing or washing methods. In 11 patients the foreskin had previously been fully retractile, in 4 partially retractile and in 4 non-retractile, whilst 4 patients had no recollection of the previous state of retractability of their foreskin. Five patients gave a past history of balanoposthitis, one of ammonia dermatitis and 6 of forcible retraction, but in each case the last episode of any one of these had been separated from the onset of phimosis by a period of years. All were fully continent by day and night. Two patients had a skin disease (psoriasis) and 3 an allergy (2 penicillin, 1 pollen). The fathers of 3 boys had been circumcised for reasons unknown. In a total of 14 brothers over the age of 5 years there were no instances of phimosis. All of the patients were prepubertal and physical examinations were unremarkable apart from the presence of phimosis, which was confined to the tip of the prepuce and did not extend from more than 0.25 cm proximally.

Operative Findings

Adhesions between the glans and foreskin were present in 6 cases and retained smegma in 2 cases. The underlying glans appeared normal except in one patient where there was a suggestion of involvement of the urethra meatus.

Laboratory Findings

An excess of leucocytes in sterile urine was found in one patient, but in the remainder the urine was free of bacteria or other abnormal constituents on routine laboratory testing. Pathogenic bacteria were cultured from the prepuce in 4 instances (beta haemolytic streptococci 2, Proteus 2). In other cases culture was either sterile or produced mixed growths of conventionally non-pathogenic organisms.

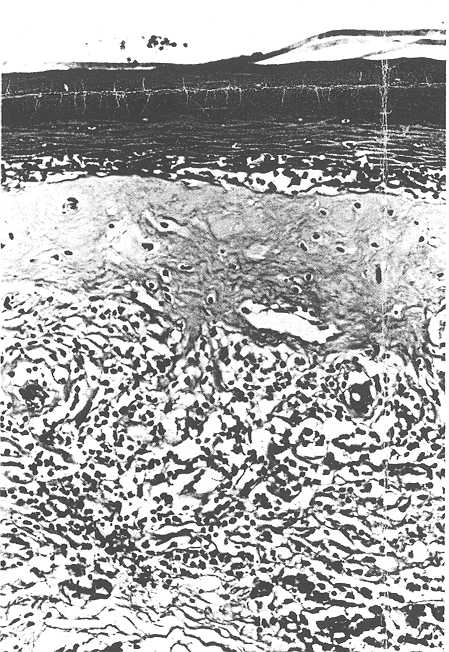

Histological Findings

Twenty-one specimens were submitted for histological examination, all but one of which showed the features of Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans (BXO). The histological criteria for this diagnosis was oedema and homogenisation of collagen in the upper dermis, inflammatory infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the mid-dermis, atrophy of the stratum malpighi and hydropic degeneration of the basal cells (Bainbridge et al., 1971; Lever and Schaumburg-Lever, 1975). A typical example is shown in figure 3. The only atypical finding was that although the stratum malpighi was atrophic in some areas, other parts of the epidermis were of normal width or even acanthotic. A patchy non-specific outer dermal infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells was often present in other parts of the prepuce not affected by BXO. The single specimen not affected by BXO had minimal chronic inflammatory changes in the outer dermis and marked dilation of the lymphatic channels near the inner surface of the prepuce. The foreskins of 11 other boys aged 8 months to 11 years, who had been circumcised for religious reasons, were also examined histologically: none showed the changes of BXO.

The findings of a previous survey (Rickwood, 1977) confirm that phimosis in the pathological sense is rarely seen in pre-school boys. Its aetiology remains obscure. Our data do not support previous contentions that it is due to forcible retraction, ammonia dermatitis or recurrent balanoposthitis. There appears to be no familial predisposition or any relation to the changes of puberty, nor is there any evidence of its being a form of contact dermatitis, a local manifestation of general allergy or a reaction to retained smegma. It is not related to the presence or otherwise of preputial adhesions. If a bacterial organism is involved it is not a conventional pathogen. A viral aetiology remains a possibility.

The finding of BXO is almost all cases was unexpected, since this is a condition mainly reported in adults and childhood cases have been thought to be exceptional. (Caterall and Oates, 1962; Schinella and Miranda, 1964; Mikat et al., 1973; McKay et al., 1975). BXO histologically resembles Lichen Sclerosis et Atrophicus, and may affect the prepuce (Bainbridge et al., 1971), the anterior urethra (Staff, 1970) or both simultaneously. Although there are changes in the dermal collagen, there is no evidence that the condition is related to the general collagenoses (Leven and Schaumburg-Lever, 1975), and the notion that is is primarily an inflammatory disease is supported by the lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltration which is especially marked in its early stages (Staff, 1970). If so, however, the nature of the inflammatory agent is unknown.

It has been assumed that acquired phimosis persists or progresses. In this series, where all patients were circumcised within two months of presentation, no changes for better or worse were noted, but at a time when waiting lists were longer a few examples of spontaneous and apparently permanent regression were seen. On the other hand, in adult patients progression of the disease to involve the anterior urethra may occur, and the likelihood of this happening may possible be increased as a result of circumcision (Stuhmer, 1928; Staff, 1970). The literature does not contain any examples of this occurring in childhood.

These considerations have some bearing on the management. Treatment is undoubtedly required, not only for the long-term problems associated with a permanently non-retractile foreskin, but because boys with phimosis are often much troubled with their present symptoms. Although spontaneous regression may occasionally occur, and although the changes of BXO have been reversed by the local application of corticosteroids (Caterall and Oates, 1962; Poynter and Levy, 1967), circumcision is undoubtly the most efficacious treatment and there seems little reason to doubt its safetyin the long term.

![]() Note:

Note:

Kraurosis glandis et preputia penisArchiv für Dermatologie und Syphilis, 156, 613-623.

A. M. K. Rickwood, FRCS, Senior Surgical Registrar.

V. Hemalatha, FRCSE, Registrar.

G. Batcup, MRCS, MRCPath, Senior Registrar, Department of Histopathology.

L. Spitz, FRCSE, Consultant Paediatric Surgeon.

Requests for reprints to: A. M. K. Rickwood, Paediatric Surgical Unit,

The Children's Hospital, Western Bank, Sheffield S10 2TH.

Received 12 February 1979.

Accepted for publication 26 April 1979.

The Circumcision Information and Resource Pages are a not-for-profit educational resource and library. IntactiWiki hosts this website but is not responsible for the content of this site. CIRP makes documents available without charge, for informational purposes only. The contents of this site are not intended to replace the professional medical or legal advice of a licensed practitioner.

© CIRP.org 1996-2025 | Filetree | Please visit our sponsor and host:

IntactiWiki.