Seattle Times (Seattle, Washington). Wednesday, 9 July 2003.

Seattle Times (Seattle, Washington). Wednesday, 9 July 2003.

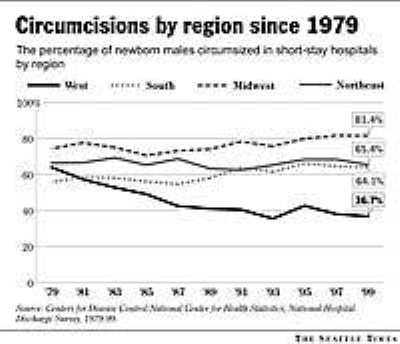

Over the past 20 years, rates of hospital circumcision have fallen steadily in Western states, as doctors and parents debate the procedure's medical and cultural significance.

The pictures were eye-catching but hard to look at: baby boys strapped down, surgical drapes across their middles revealing teeny, tiny penises clamped into metal vises, awaiting a few fateful minutes with the knife.

Are you squirming a bit? That's just fine with anti-circumcision protesters, who gathered recently with their photos and banners outside the Washington State Convention & Trade Center, hoping to change hearts and minds among hundreds of pediatricians gathered for an annual meeting.

It's barbaric,

said protester John Mark, a former public-health worker and founder of CIRC, the Circumcision Information Resource Center of Washington, who was busily buttonholing passersby.

We should protect every part of a child, from head to toe and everywhere in between—from our point of view, especially in between.

Once upon a time, the decision to circumcise a newborn boy barely warranted discussion between new parents and their obstetrician, pediatrician or family doctor. Of course,

was the answer to the doctor's virtually rhetorical question about the procedure, which removes the skin covering the head of the penis, called the foreskin.

Parents assumed there were good reasons to do it, and doctors assumed parents wanted it done. Although statistics are spotty, by the mid-20th century the practice was widespread. By 1979, says one researcher, as many as 85 percent of baby boys in the U.S. were being circumcised. In Western states, according to federal statistics, nearly 64 percent of boys born at hospitals were circumcised.

In those years, parents or doctors sometimes made vague references to supposed health benefits, but details probably were not discussed. Often, parents simply said they wanted their newborn boy to look like the other kids,

or like Dad.

Today, it's not as clear as it once was what the other kids, or even Dad, if he's young enough, will look like.

Over the past 20 years, rates of circumcision have fallen steadily in Western states. In 1999, although national rates hovered around 60 percent, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, less than 37 percent of boys born in hospitals in Western states were circumcised.

I tell people, at least in my community, that if their son was in high school and pulled his pants down in the locker room and was uncircumcised, it would be no big deal,

says Dr. Mitch Weinberg, a pediatrician and president of the medical staff at Evergreen Hospital Medical Center in Kirkland.

Twenty years ago that wouldn't have been the case.

These days, Weinberg, like many doctors, is careful to go over the pros and cons with prospective parents. I think it's a parent's choice to decide,

he said. It is not a medically necessary procedure.

Dr. Steven Woods, chief of the obstetrics-gynecology department at Overlake Medical Center, agrees. On the other hand, he says,

It's not butchery.

In 2000, Group Health Cooperative, which had not covered routine circumcision since the late 1980s, resumed coverage in health policies after merging with Group Health Northwest, based in Spokane. Many parents asked for it, and doctors were divided about the procedure's value, said Group Health spokeswoman Lee Tucker Therriault.

Considering that circumcision is a procedure that's been around for centuries—the first recorded account appears to be about 2400 B.C., from an Egyptian hieroglyph—some might think it's odd that once again, it's become controversial.

But in many ways, patients are making more decisions about medical care that was once taken for granted. And many doctors, wary of regaining that old paternalistic

label, are trying harder to present balanced information to help new parents sort out the choices, rather than just giving them their opinions. And in the past few years, anti-circumcision groups have gained new momentum.

Lawsuits over technically flawless circumcisions on babies may signal even more change on the horizon. One was filed by an adult man who claimed he was sexually desensitized without his consent, the others by parents who said they weren't fully informed about the procedure.

For some parents, circumcision isn't really a choice: It's dictated by their religion, or there are specific medical indications for the procedure.

For most parents, though, the decision they face is about routine neonatal circumcision. For many, it's a decision that requires more analysis than it did for their parents.

Lon Vaughn and his wife, Jennifer, were divided. She was of the if it's natural, leave it alone

view, he said. But Lon prevailed, he said, because he'd once been a boy in gym class and knew how important it was to be normal.

It's hard enough for a kid to grow up,

says Vaughn, a small-business owner who lives in Ballard. The last thing you want, he says, is to draw attention to your genitalia.

Being laughed at, he thinks, could scar a boy for life.

Vaughn figures that his son, due next month, will mostly see circumcised men in pictures, or in real life. On the other hand, an uncircumcised friend opted against the procedure for his baby. For both of them, he realized, it was important that their sons look like their dads.

Katlyne Mobasher, an Edmonds mom, decided against it for her son, now 13, after reading about circumcision when she was pregnant. The whole thought of it didn't seem like a very nice thing to do to a baby,

she said. After all, she'd strongly disagreed when a friend had docked her dogs' ears and tails—for no good reason, she thought at the time.

She learned that the vast majority of men in Scandinavian countries aren't circumcised, and seemed to be healthy and strong, said Mobasher. And the look like Dad

argument didn't impress her either: If your husband was missing an arm, would you chop off your baby's arm?

In 1999, the American Academy of Pediatrics took a long look at the evidence and concluded the potential benefits of circumcision, weighed against risks, weren't significant enough to recommend it as a routine procedure. They stopped short of advising against it, but recommended that parents weigh potential benefits and risks, as well as cultural and religious traditions.

In many other countries, circumcision is much less common, and health insurance doesn't routinely pay for it. In Canada, for example, estimates place the rate of circumcision at 20 percent or less.

Potential benefits, says Dr. Monja Proctor, a pediatric surgeon with Swedish Pediatric Specialty Care, are thought to be decreased incidence of urinary-tract infections and penile cancer, a very rare disease in men. Circumcision also may help protect men from getting and spreading sexually transmitted diseases, including AIDS, although the pediatrics academy statement calls that evidence complex and conflicting.

On the other hand, there are real risks, including what Proctor calls acute, significant complications.

Bleeding and infection may range from mild to severe. Other complications may not show up until much later, including scarring or stricture of the opening of the urethra.

Although most studies show that serious complications are very rare, John Geisheker, a local lawyer, says he now has several botched-circumcision clients,

and that a pediatric urologist he consults told him he sees three such cases every day.

Ranging from very mild to severe, complications may reach as high as 3 to 4 percent, Proctor estimates. Weinberg puts the risk of complications lower, probably under 1 percent, while anti-circumcision forces often use higher estimates.

Proctor believes most of the touted benefits can be achieved other ways—through proper hygiene and, in the case of urinary-tract infections, antibiotics. As for the supposed protection from sexually transmitted diseases conferred by a circumcision, Proctor says it doesn't stack up against safe sex.

I don't try to scare parents, but you're doing essentially an elective procedure with very few definite indications, and it has some potential real risks,

says Proctor. Putting a child through circumcision because you say you're decreasing the chances of a sexually transmitted disease is, I think, a very poor indication.

Other cosmetic procedures are done to fix abnormalities, she says. But this is not an abnormality.

Like many doctors these days, though, Proctor believes it's the parents' right to decide.

There's not a right or a wrong answer,

she says. I think it's important to consider what the risks are, and what the reasons are they're proceeding with a circumcision.

Dr. Jeffery Thompson, chief medical officer for the state's Department of Social and Health Services, points out information about circumcision made available to doctors by

MD Consult Clinical Knowledge System, an online service.

The foreskin on the penis is not some cosmic error,

says the fact sheet. The foreskin, the fact sheet continues, protects the top of the baby's penis from urine, feces and other irritation, lessens the chance of infection or scarring of the urinary opening, and helps preserve the sensitivity of the glans, the top of the penis.

On the other hand, it notes the sensitivity of adolescent boys to looking like everyone else: It can be emotionally painful to be a trailblazer about the appearance of one's genitals.

At Evergreen, Weinberg says he tells parents that research shows it's not necessary for kids to look like their fathers, but once you make a choice, stick to it for siblings. Little brothers pull their pants down, and they want to look alike.

There are huge variations in circumcision rates by country and by region, and even by hospital, Weinberg notes. At Overlake Hospital in Bellevue, hospital figures for 2002 show two-thirds of baby boys born there were circumcised; at Swedish Medical Center's First Hill and Ballard hospitals, the rate is about 56 percent, including babies circumcised later at doctors' offices. Some observers believe the West's lower statistics may reflect ethnic differences; for example, California has an increasing proportion of Hispanics, who historically have been less likely to choose circumcision.

The numbers also may reflect that California, like Washington, has not covered routine circumcision with Medicaid, the joint state-federal health-insurance program, for many years.

It's not clear yet what effect the lawsuits may have on numbers of circumcisions. One suit, by the parents of a North Dakota boy who said a Fargo doctor didn't inform them of the risks, is on appeal after being rejected by a jury.

Another, by a 21-year-old Virginia man, William Stowell, targeted the hospital where he was born.

Stowell, who received an undisclosed amount of money in settlement, said his foreskin was wrongly removed, sexually desensitizing him without his consent. He believes doctors shouldn't do circumcisions, even if parents ask them to.

Common sense should dictate you shouldn't perform life-altering surgery on someone for no medical reason,

said Stowell, reached last month at an anti-circumcision group's strategy meeting in San Francisco. You don't perform cosmetic surgery on your child to make him look like you.

Stowell says his lawsuit should send a stab of fear into doctors who do circumcisions. I was circumcised in 1981. It was 18 years before they heard from me again,

he says. The doctor could be living the high life in retirement

when an angry patient appears with a lawsuit.

Geisheker, the attorney, sees the lawsuits as the leading edge of a movement. Parents, Geisheker believes, depend on the goodwill and honesty of doctors to guide them. They shouldn't have to spend evenings reading urology texts to protect their child from medical overreaching,

he says.

Proctor predicts the trend will be toward fewer circumcisions as parents realize there is no medical justification. Then there will be less of a cultural tendency to do it.

Doctors, too, are changing in their views, says Dr. George Denniston, a retired UW family practitioner and tirelessly campaigning president of DOC (Doctors Opposing Circumcision).

Denniston, co-author of Doctors Re-examine Circumcision,

says that's evidenced by doctors' attitudes toward anti-circumcision protesters. In the old days, they'd come up and say

Get a life!

Now, they can't do that—they can't trivialize it.

In the old days, so went the theory, babies didn't feel the pain of a circumcision.

Now, doctors say, they know better. For one thing, babies who don't receive some pain relief develop a more pronounced response to future pain, says Dr. Monja Proctor, a pediatric surgeon with Swedish Pediatric Specialty Care.

They should all definitely have anesthesia —not a general, but some type of local anesthesia,

says Proctor.

Dr. Steve Woods, chief of the ob-gyn department at Overlake Medical Center, says two decades ago when he went through residency training, anesthesia wasn't used.

It was horrible.

He has a hard time believing people used to think babies didn't feel pain, he says. Anybody who's ever done one circumcision knows that's full of baloney.

For the past 10 years, he's been using pain relief, and at least for some babies, it makes a big difference. The one I did this morning, the kid just slept through it,

he says.

On the other hand, both doctors say, anesthesia doesn't always work that well, and reactions vary from baby to baby. Even with an excellent nerve block, it's not a pain-free procedure,

says Proctor.

Anesthetics commonly used include:

The Circumcision Information and Resource Pages are a not-for-profit educational resource and library. IntactiWiki hosts this website but is not responsible for the content of this site. CIRP makes documents available without charge, for informational purposes only. The contents of this site are not intended to replace the professional medical or legal advice of a licensed practitioner.

© CIRP.org 1996-2026 | Filetree | Please visit our sponsor and host:

IntactiWiki.